At the African Studies Association meeting in Chicago, I participated in a panel on “everyday trades.” I did that thing where I changed my paper title at the last minute, because as I was putting together my slides I was really struck by memories of how warm, sociable, and special the markets I visited were, and I wanted to draw that element out. So the talk became “At Home in the Market: Fashion, Identity, and Reputations in West African Networks of Cloth.”

In the paper I argued that shorthand notions of identity (stereotypes and reputations) are used as narrative strategies in the markets of Malian goods in a few different ways. One, cloth is flowing in great quantities, a commodity, and both sellers and consumers have a stake in making the items unique, special, “singularizing” them in the term of Igor Kopytoff (1986). Two, in this setting where there is little power and sometimes not much solid information, national and ethnic reputations are a language of credibility. I mainly discussed the Marché Malien in Dakar (actually in a few places), and I compared it with sketches of markets in Ndiassane (a temporary market in a pilgrimage town) and in Paris.

The cloth dyed in Mali is believed to be the best quality, despite vigorous dyeing activity in Senegal (and despite some of the cloth in the Mali market being dyed locally in Senegal). The bazin comes folded uniformly, in plastic packets, and the sales procedure is to whip them open, crackling and shining, to illustrate the full impact of each one. It also allows sellers to assert the quality of their wares (and buyers to evaluate it visually and through touch).

All the merchants in the Mali Market speak Bamanankan, even the Peuls from Guinea, the Soninkes from interior Senegal, the Maures from rural Kayes region and Mauretania, the Tamacheq from Tombouctou (who told me he had to learn Bamanankan in Dakar to communicate with his compatriots). In this market, language becomes an overriding identifier, and Bamananakan language becomes a metonym for Mali. (It’s sometimes also called the Marché Bambara.) The image of the Malian cloth—the skilled dyer in Bamako, the Malian tastemakers producing new styles of surface decoration, the numerous music and media stars who wear the shiny stuff—all of that distinguishes it from others, and so being located among other Malian merchants, speaking Bamanankan and demonstrating one’s Malian connections, are important claims to the authenticity of the product through the credibility of the seller. I even know a Senegalese dyer-designer, Cheikouna, who has been known to speak in his limited Bamanankan when in markets, to better “market” his wares by temporarily putting on that Malian reputation.

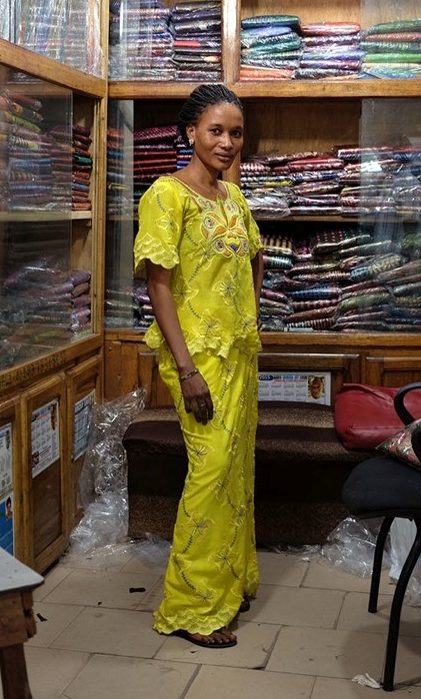

“Malianness” of the sellers and the cloth is a selling strategy, but it’s also genuinely powerful and affecting: one merchant, Dede, told me about the pride she feels when she sees images of African presidents and celebrities wearing Malian bazins. Dignity and personal appearance also matter as “bon marketing“–asserting who you are, not just showing off the wares like a mannequin. All the marketplaces I visited are relentlessly social spaces. The merchants from Mali strive to develop local networks of clients and neighbors while maintaining Malian or “Bambara” identity. For their compatriots also living abroad or in transit, the Malian merchants offer access to things that are familiar-yet-distant.

My colleague Sarah Monson was also on the panel, presenting her research in the Kumasi Central Market. We had a lot to say to one another. That’s what I enjoy about ASA–I’m not with only art people all the time and can sample lots of other fields.