I was invited to give a talk at my alma mater, Miami University, by the fabulous people in the art museum. The talk aligned with a senior art history capstone project, a reflexive exhibition of African art that probed modes of African art display, collecting, and knowledge creation. Many thanks to the Art Museum and congratulations to the students and their prof, my former adviser dele jegede.

I was invited to give a talk at my alma mater, Miami University, by the fabulous people in the art museum. The talk aligned with a senior art history capstone project, a reflexive exhibition of African art that probed modes of African art display, collecting, and knowledge creation. Many thanks to the Art Museum and congratulations to the students and their prof, my former adviser dele jegede.

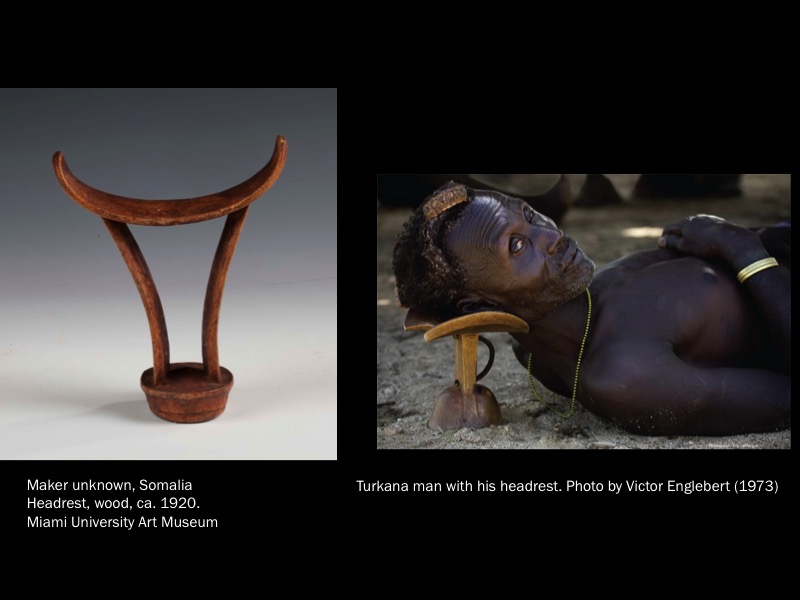

In the talk I outlined some of the history of display of what we now usually call African art, and the kinds of knowledge those conventions privilege. They give us clues for how to behave, how to look, and how to understand what we see. I began with some field photographs to talk about the density of African art, by which I mean both that there are many layers of meanings and use, with fuzzy edges, in many African art works, and that the works are closely imbricated into life experiences. Influenced by other projects I was then working on, I also discussed cultural paradigms of “art” and “craft” (and their sibling concept-pairs, expressive and functional, decorative and useful, original and traditional) and how they run aground here.

Looking through an impressionistic survey of historic and current installations of African art, I focused on the kinds of looking experiences that museological techniques invite or discourage, and the intellectual borders and habits of thought the also display. (Lots of interesting stuff in the book Representing Africa in American Art Museums.) I wondered how sensuous seeing and factual reading could be brought together, and if the individual or the agency of an artist or original owner could be imaginatively recaptured in a gallery, or if those worlds are too divided. (I sort of think both things are true.) The power and the problems of technologies like photography, video, and sound are worth exploring more deeply. I touched on them in the talk, noting that despite the issues they bring in terms of accessibility, rights, conservation, and probably other things too, and despite the deficiencies of a little photo or screen, the feebleness of a compression-crunched video clip, I feel it is imperative to include them. To gesture toward that context for the purpose of richer education for visitors and in the spirit of ethical recognition of African artists and communities, a turning from the anonymous, severed past of African art history.

Looking through an impressionistic survey of historic and current installations of African art, I focused on the kinds of looking experiences that museological techniques invite or discourage, and the intellectual borders and habits of thought the also display. (Lots of interesting stuff in the book Representing Africa in American Art Museums.) I wondered how sensuous seeing and factual reading could be brought together, and if the individual or the agency of an artist or original owner could be imaginatively recaptured in a gallery, or if those worlds are too divided. (I sort of think both things are true.) The power and the problems of technologies like photography, video, and sound are worth exploring more deeply. I touched on them in the talk, noting that despite the issues they bring in terms of accessibility, rights, conservation, and probably other things too, and despite the deficiencies of a little photo or screen, the feebleness of a compression-crunched video clip, I feel it is imperative to include them. To gesture toward that context for the purpose of richer education for visitors and in the spirit of ethical recognition of African artists and communities, a turning from the anonymous, severed past of African art history.

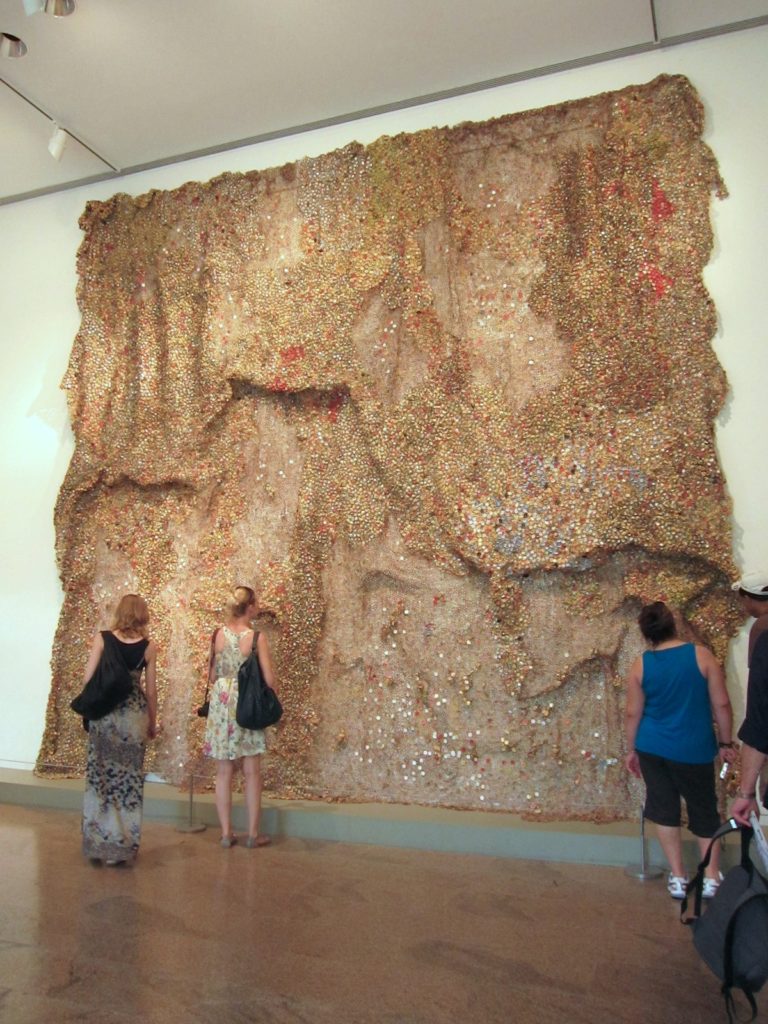

It’s rare, I think, that you look at a work of human manufacture and it really sings out to you with personality, intelligence, and heart. Tactile experiences, relationships, and knowledge have been brought to bear on some material, and here is a result. To be pedantic, or simply precise, there is no “recovering” African context—anything we apply to artworks, even the ways they sometimes seem to act upon us with a will of their own—this is imaginary contact. Nevertheless I think this contact is valuable, and the more we know about our objects and about the ways we are seeing them, the richer this contact can be. With our open attention, African art objects themselves can dissolve and scatter the museum’s categories and free the imagination.